4 min read

How money laundering threatens the ‘least corrupt’ nations on earth

![]() AML RightSource

:

February 18, 2020

AML RightSource

:

February 18, 2020

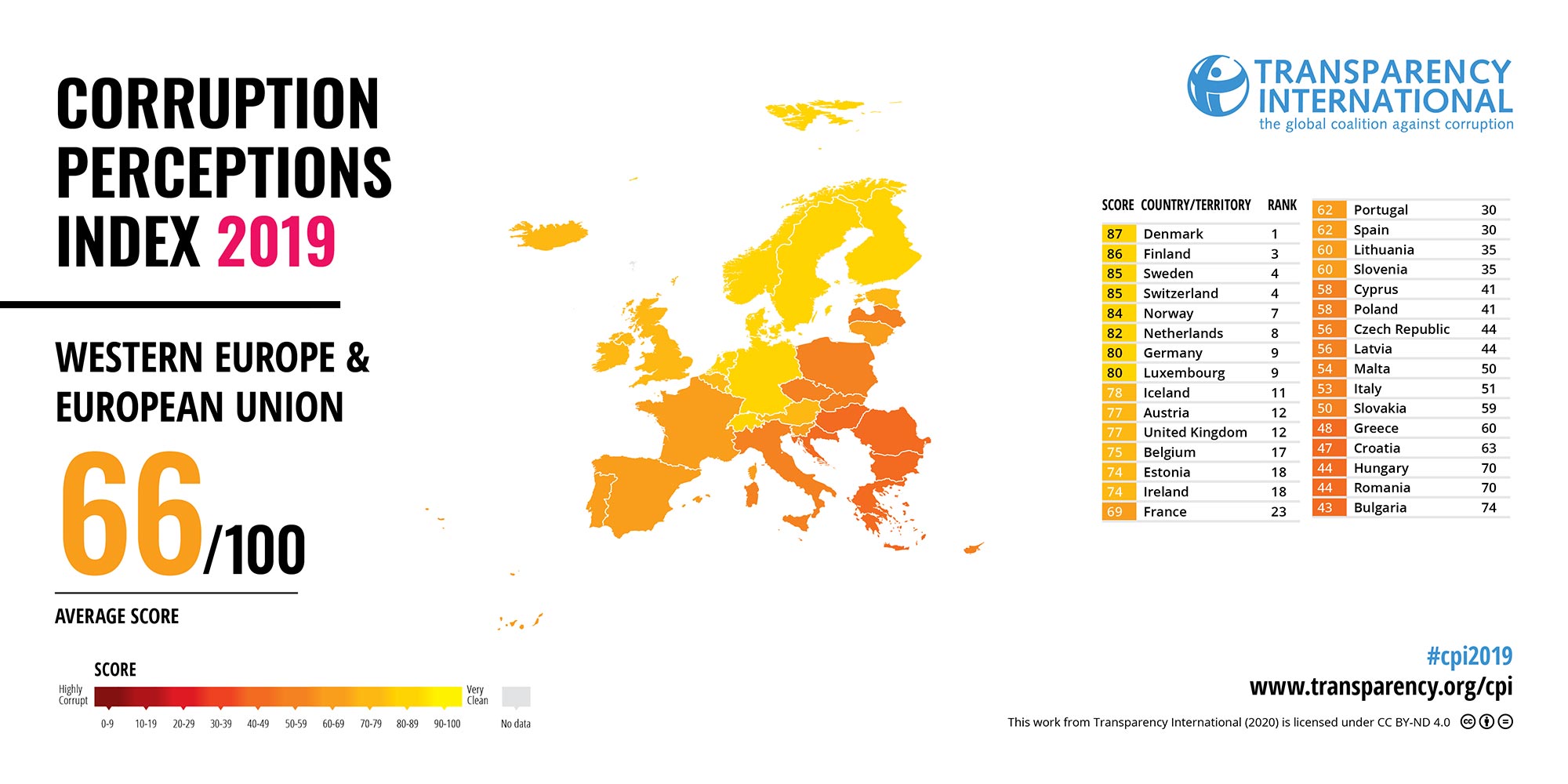

Come January each year, the issue of global corruption comes under the media spotlight. The reason – the annual release of the Corruption Perceptions Index (CPI) by the global watchdog Transparency International.

Newspapers around the world churn out articles indicating the latest ranking of their home country. This year, it was the turn of nations like Greece, Guyana, and Estonia to celebrate significant improvement in their rankings.

The world is stuck in limbo in the fight against corruption

Those three are part of an exclusive group of 22 nations who have managed to improve their scores by “significant margins.” They are the only nations to have improved their anti-corruption scores in the last eight years.

But for the vast majority of the 180 nations surveyed by Transparency International, the results are underwhelming, if not downright alarming. The changes, if any, in their corruption rankings remain minimal.

And even more dismal is the fact that in the same period, 21 nations experienced downgrading on the CPI index due to an increase in corruption. A cursory look at CPI reports over the decades indicates that the world is generally caught in limbo in the fight against corruption.

The contrast between the Nordics and Sub-Saharan Africa

The CPI has a scoring system of 1 to 100, with lower scores indicating high levels of corruption. More than two-thirds of the countries have their scores below 50. Among these, the worst affected are the nations wracked by poverty, violence, and political instability.

The regions of Sub-Saharan Africa, North Africa, and the Middle East have the most candidates in the bottom 10 list, with countries like Libya, Sudan, Equatorial Guinea, Syria, Yemen, and South Sudan languishing here. Somalia is officially the most corrupt nation on earth, since 2015. All these nations have a score under 20.

At the other end of the table, there are 59 nations with scores in the top half, with nine of them scoring 80 or above. With the exception of New Zealand and Singapore, all others in the top 10 are from the European Union.

Even inside the EU, one region stands out for its low levels of corruption in the public sector – the five Nordic nations of Denmark, Sweden, Norway, Finland, and Iceland. They all have the same defining characteristics – strong democratic institutions, high economic development, and relatively smaller populations.

Even the leading nations are not immune to corruption

In most afflicted nations, corruption exists in the public sector, government institutions, and politics. The symptoms include bribery, corrupt business deals, political decisions influenced through campaign financing, embezzlement, and more.

While these symptoms are rife in regions like the Asia Pacific, Middle-East and Sub-Saharan Africa, Western Europe has a relatively clean record in the public sector. But the operative word here is “relatively.”

But the top-ranked nations are not immune to corruption. In fact, the experience in recent years indicates that the rich, stable nations are vulnerable to one particular form of financial crime – money laundering.

In the last decade, the European Union has emerged as a favored haunt for money launderers across the globe. Numerous scandals have exposed the corruption gnawing at the financial and banking systems in the region.

The trans-national impact of money laundering in EU

The very act of money laundering often involves the shifting of vast sums of money across international borders. It is a form of corruption that transcends borders. And it also has a multiplier effect on corruption wherever it goes. The cash transferred as part of money laundering is used in bribes, campaign finance, and other ways to garner influence.

European banking and financial systems are highly integrated. But it lacks the same level of integration when it comes to supervision and monitoring of illegal cash flows. This has inadvertently led to the creation of hotspots for money laundering, in the unlikeliest of places.

The Nordic nations, Germany, and the Netherlands are all ranked comfortably in the top 20 of the CPI index. And these nations have also witnessed some of the biggest banking scandals in recent history.

Regional banks like Danske Bank, Swedbank, Deutsche Bank, and ABN Amro have all been caught up in money laundering scandals. According to Europol, the primary source of the illegal cash flows in all of these cases was Russia, ranked 128 on the CPI with a score of 28.

The role of the private sector in promoting corruption

The EU clearly has a problem with money laundering. And the last few years have seen drastic action from Brussels, with strict new regulations like the AMLD5 adding teeth to agencies fighting this form of corruption.

Enforcement remains a significant challenge though, particularly in the private sector, where things are not so “clean” even in the Nordic nations. The banks there are not the only ones caught red-handed.

There are at least two major incidents where Nordic companies were caught giving bribes to officials in other nations. Samherji, an Icelandic fishing conglomerate, bribed officials in poor African nations like Namibia and Angola, for local fishing rights.

An even bigger name in Sweden, the famous Ericsson telecom giant, was caught by US authorities for bribery campaigns in several Asian and African nations. They had to pay a $1 billion fine to settle all charges.

In many of these instances, money laundering and shell corporations played a huge role in facilitating the cash flows. In the Samherji case, in particular, a state-owned bank DNB of Norway has been heavily implicated.

Conclusion

These instances show the universal nature of corruption in human societies. Having a clean public sector is no guarantee against this menace, as the Nordic experience tells us. In many instances, we can see companies “exporting” or “promoting” corruption in lower-ranked nations for private gain.

This is particularly odious, as it prevents those countries from getting out of the morass. The so-called “cleaner” nations in Europe also serve as a haven for corrupt individuals and their illegal wealth from nations in Africa, Middle-East, and Asia-Pacific.

For countries in those regions to have a better chance of combating corruption, the authorities in the EU need to step up. Stricter regulations need to be backed up by improved monitoring systems, involving modern digital technologies and better cooperation between the public and private sectors.